|

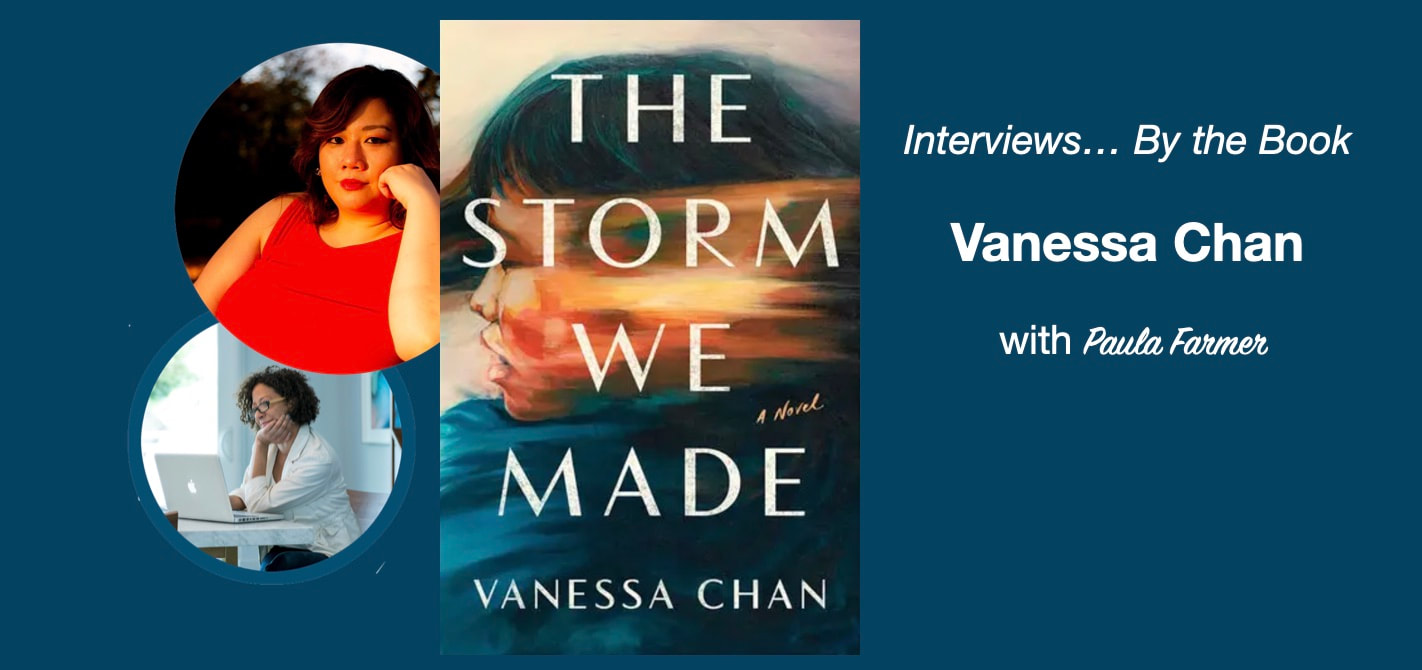

Vanessa Chan is the author of The Storm We Made, a January 2024 debut fiction release from Simon & Schuster Books

1945 In British-colonized Malaysia, Cecily is the dutiful wife to her husband who is a low level government bureaucrat, and the mother of four. During this pivotal year of WWII, Cecily’s family is in danger in disparate ways and for varied reasons. As far as she is concerned, she is responsible for all the havoc, she must rectify the situation, and her family must never know the truth. Ten years prior, as a bored housewife, Cecily craved for more in her lifehad been desperate to be more than a housewife and a chance meeting with a charismatic General lured her into a life of espionage, pursuing dreams of an “Asia for Asians.” Instead, Cecily helped usher in an even more brutal occupation by the Japanese. Fast forward several years as the war is drawing to an end, the consequences of what she thought was a noble role have taken hold of her and her family in disastrous ways. Spanning years of pain and triumph, and told from the perspectives of four unforgettable characters- fifteen-year-old Abel who has disappeared, as too do so many boys his age in their village; Jasmin, is confined in a basement to prevent being pressed into service; the oldest sibling, Jujube, works at a tea house frequented by drunk Japanese soldiers, is overcome with resentment. The Storm We Made is a unique examination of a little-known aspect of WWII. From the first character and situation, one is drawn in and fully committed. In the novel, the reader is given insights into the horrors of war; the complex relationships between those that are colonized and the colonized; the oppressed and the oppressors. But mostly the novel’s points of view give credence to the ambiguity of right and wrong. The Storm We Made shines a light on the brutality of war, the pain of occupation and the resilience of survivors. Chan delivers a fresh and necessary voice on the literary landscape.” Author, Vanessa Chan was born and raised in Malaysia. Her short stories have been published in Electric Lit, Kenyon Review, Ecotone, and more. She was the 2021 Stanley Elkin scholar at the Sewanee Writers Conference and has also received scholar awards to attend the Bread Loaf and Tin House writers’ conferences. The Storm We Made is her first novel. Paula Farmer is a book reviewer and author event host/coordinator for Book Passage in San Francisco, California. Below is Farmer’s brief review of the novel and her interview with Chan about the family stories the author felt compelled to preserve in writing. Paula Farmer: What was the inspiration for and driving force behind the story development — the historical events or the characters? Vanessa Chan: The stories in The Storm We Made definitely have their foundations in some of the stories that my grandmother and family have told me. But some stories are also drawn and dramatized from history, while other parts are built from the imagination, as novels do. As the eldest grandchild on my father’s side, I spent a lot of time with my grandparents, and over the years, I would glean fascinating and often horrible anecdotes from my grandmother, delivered in a matter-of-fact way. One such anecdote — when she was thirteen years old, as she was cycling home, she missed by thirty seconds, a bomb from an air raid that fell right behind her bicycle. She told me with an almost childish glee, how her siblings who had not realized she’d made it home, dug in the rubble for hours looking for her bits of her, thinking she had died. When I finally started writing this book, during the earliest days of 2020 (the part of the pandemic when things were at their worst), no libraries and archives were open. Instead, I relied on my memory, and the stories I had heard before from my family, that I had internalized but never really put to paper. In doing so, I realized I knew more than I thought I did. My uncle mailed me a book of old photographs of Malaysia. Eventually, when I was finally able to return home, I was able to check a lot of things with my grandmother before she passed. My father, a history buff, fact-checked many details such as the kind of dishware and shoes that were used in the 1930s and '40s. I suppose, true to form, my novel became a family affair. Funnily enough, because my novel features a woman spy at the center of it, people tend to ask me now if my grandmother was a spy. There weren’t any spies in my family…as far as I know. PF: Historical fiction seems to have the additional element of a lot more research than other genres. Given that, what prompted you to take on that ambition for your debut? What did you find yourself more attracted to in the writing process — the research or the writing? VC: I’m one of those people who believe that stories call out to the writer. I felt called, in fact compelled, to write these stories. The research was what helped keep the stories honest and true to their time. It felt imperative to me that I write these stories down, to preserve them and make a record of lives and histories lived. But it was equally important to me that the stories be honest, and that they also made a great read. Books exist for noble purposes to inform and illuminate, but in the end, they also need to entertain! PF: You present a widely known piece of history (WWII), but from a very unique perspective. Why was it important to you to present an aspect of this history from the POV of [those] marginalized? VC: I am a descendent of a colonized people who have survived occupation. Colonization quite literally lives in us. But Malaysian grandparents and ancestors are reluctant to dwell on these traumatic and challenging times, which means that their stories could get lost with time. It is important to me that their stories make their way into the historical record — stories only become history when they’re written down, so I did. PF: This novel is rich with several interesting characters from multiple points of view. Why did you write it this way? VC: The Storm We Made is written in alternating viewpoints of four characters — Cecily, a mother and spy, and her three children, Jujube, Abel, and Jasmin, each of whom encounters a different fate. I come from a noisy, dramatic family where everyone is always talking at the same time. For that reason, I think I’ve always enjoyed stories with multiple points of view — ones that seem often disparate but come together in the end. That’s how I wrote my novel. I had too many stories to tell, and a single point of view felt limiting to reflect the breadth of the story, the amount of time I had to traverse to tell the story, and the multiple geographic locations my characters exist in at the time. I also used the multiple points of view to reflect the different ways that my characters encountered a member of the colonizing Japanese population, and how these different relationships change my characters. PF: Who are the authors and/or books that inspire you in general and this writing project specifically? VC: I enjoy reading and writing fiction that is a bit wild — stories that are shocking, feral, or make me uncertain who the hero is. I love a book where there’s some uncertainty about who or what is good and bad, because that feels more human; as humans we exist in uncertain, gray areas and I believe that morality is entirely dependent on circumstances. A few of my favorite ambiguous literary protagonists are the room salon women in Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face, the twins in Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, and the bumbling windshield wiper entrepreneur in Kirstin Valdez Quade’s The Five Wounds. With The Storm We Made, in addition to these books, I also drew inspiration from novels like Homegoing and Pachinko — books that illuminated lesser-known histories, but without sacrificing the story — which is why we come to fiction in the first place. Title: The Storm We Made Author: Vanessa Chan Publisher: Marysue Rucci Books/ Simon & Schuster Format: Hardcover Genre: Historical Fiction Release Date: 1/2/2024

0 Comments

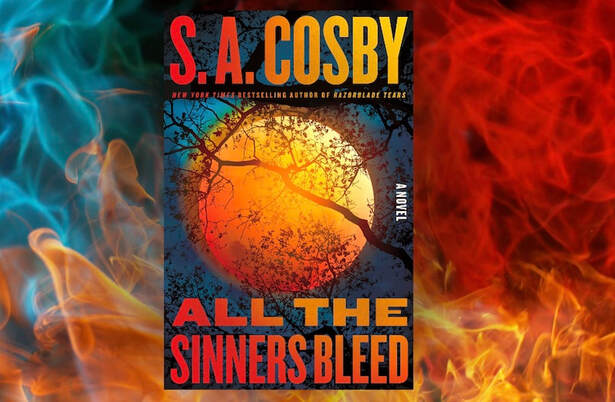

In Southern Noir fiction writer, S.A. Cosby’s latest novel maintains his laudable pattern of mixing a deft and detailed crime mystery with vital and current social issues. He does so by telling a compelling story that is driven by richly layered, complex characters. In “All the Sinners Bleed”, the protagonist, Titus Crown is the first Black sheriff in the history of Charon County, Virginia. He came to the position after years of living in Indiana as an FBI agent. He left the agency and moved back to his hometown in the aftermath of his father’s stroke. Being there longer than he expected, he decided to settle in and found himself campaigning for the sheriff’s position. Between his experience in law enforcement and native to Charon County, Titus knows better than anyone that while his hometown might on the surface seem quaint and full of Southern charm, it is actually steeped in racism and secrets.

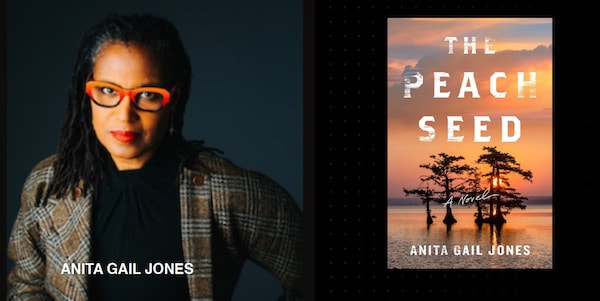

At the first anniversary of Titus’s election, a school teacher is killed by a former student and the student is fatally shot by Titus’s deputies. Those festering secrets are now out in the open and ready to tear the town apart. As the investigation gets underway, he unearths terrible crimes and a serial killer who has been hiding in plain sight. To make matters messier, local churches and their members and/or leadership, may be at the core of the crime. Along the way, Titus comes up against and is often impeded by some of the town’s white residents who were skeptical of a Black man running the department. Likewise and just as frustrating for Titus are some of the Black residents and leaders who voice concerns that Titus will stand up for and protect his own community. What Titus wants is block out the pressure and politics to run a thorough and honest investigation for the victims and their families. ‘Small towns are like the people that populate them. They are both full of secrets. Secrets of the flesh. Secrets of blood. Hidden oaths and whispered promises that turn to lies just as quick as milk spoils under a hot summer sun. The myth of Main Street in the South has always been a chaste Puritanical fantasy. The reality is found on back roads and dirt lanes under a sky gone full dark with no stars. In the back seat of rust mottled Buicks and the beds of ramshackle trucks. The heart of Charon County beat in time with the spirituals sung in church on Sunday morning. But it's soul is a truth that can scared from the sweat of illicit lovers, the blood that drops from the lip of the PTA president after her husband has had one too many too many times at The Watering Hole. It can be angered from the serial numbers on the 10's and 20's passed from the hands of Charon's favorite sons and daughters to the men and women who sell them a taste of the quiet that sends them on to dream land drooling. It's there dancing among the fumes of a kerosene heater in a freezing trailer that snatches the breath from a mother, a father and a baby boy.’ With any good mystery, it is the crime and the setup of the investigation that lures the readers in, but it is the investigator, his/her journey and supporting cast getting to the truth and executing justice that keep us turning the pages. Like previous titles by S.A. Cosby’s, “All the Sinners Bleed” is powerful, gripping and outright unforgettable as he navigates race, racism and faith. The only thing that can be better than reading it, is listening to the audiobook narrated by Adam Lazarre- White. He masterfully portrays a cast of characters ranging in age, gender and race. S.A. Cosby is the New York Times national best selling award-winning author from Southeastern Virginia. His other books include Blacktop Wasteland, In “The Peach Seed,” author Anita Gail Jones wonderfully and lovingly immerses readers in the world of Fletcher Dukes and his family, their ancestors, their scars and their triumphs. This is a multigenerational story that explores the roots of a Georgia family’s tradition and how their children ultimately carry the weight of personal matters like family secrets, along with broader social and political matters such as the America’s Civil Rights Movement and the impacts of enslavement.

The story opens in 2012, with a seemingly routine scenario for the 70-something widower, Fletcher, as he and his older sister, Olga are grocery shopping at the Piggly Wiggly ( love the specific southern references like this). It doesn’t take long before this mundane task morphs into something much more as Fletcher notices an old flame, the love of his life, Altovise Benson in one of the store aisles. Back in the day, Fletcher and Altovise were hand-in-hand for sit-ins and marches, but their plan to take their relationship to the next level was interrupted when the police turned a peaceful protest violent. Separated initially by arrest and imprisonment taking them to different towns, they would eventually be released, but their relationship never the same. Soon after, Altovise rejects Fletcher’s marriage proposal, leading to what would be a separation spanning over 50 years. Before their inevitable break, Fletcher carves Altovise a monkey from a peach seed, embellished with diamond eyes. We learn this is a tradition hailing back from an undiscovered Dukes ancestor who was sold into slavery who carved the first one—the Peach Seed Monkey -that forms the talismanic tradition. It became the rite of passage that each generation of Dukes men gifts to his son upon entering his teen years. Fletcher giving one to Altovise, creates a break in a tradition that irrevocably shapes the lives of future generations including Fletcher’s daughters and his grandson, Bo-D. Through carefully crafted flashbacks, we learn about Fletcher’s history with Altovise, their Civil Rights activism and the Dukes’ patriarch, Malik who was captured from Senegal and sold into slaver in the 1800s. Most of the book focuses on the current family and their contemporary issues such as Bo D’s struggle with addiction, and Olga’s discovery of Siman, a male relative who was put up for adoption soon after his birth in Michigan. While the different generations, characters, locations and periods portrayed in the novel, in addition to its varied themes may seem like a lot to navigate, Ms. Jones intertwines it all with aplomb. She wisely places the greater emphasis on the modern stories and characters, treading lighter with Malik’s story. Throughout, not only is there never the feeling of being overwhelmed, but more so “The Peach Seed” is wholly engaging with fully drawn characters easy to invest in. Keeping in mind, that among the noteworthy characters, not least of which is the area of South Georgia itself. Wether the narrative takes you to in Africa, Michigan or Georgia, there is an unflinching and admirable sense of place as highlighted in the passage below, the opening of chapter one. Albany. A southern city running on country fuel. Divided east to west by the Flint River, this corner of southwest Georgia is graced with majestic pecan groves and wildflower carpets buffered by blue skies; a region where flip sides coalesce, modern and antebellum, old growth and Johnny-come-lately. A place of long, deep pain, still refusing forgiveness; and yet propelled by joys and triumphs. In many ways, even in 2012, life here was the same as it was fifty years ago: a patchwork of citizens-from farmers and businesspeople to college students-going about their days as any other, separate and unequal. Although “The Peach Seed” is its own unique story, it laudably follows in the tradition of recent literary fiction gems such as Jesmyn Ward’s “Sing, Unburied, Sing” and Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing”. Those titles are shorter than that of the little over 400 pages of this new novel, but even at its hefty page count, “The Peach Seed” is a deeply satisfying read, and may even leave many wanting more. Either way, more is what we want and expect to see from this impressive debut novelist, Anita Gail Jones. Title; The Peach Seed Author: Anita Gail Jones Publisher: Henry Holt/Macmillan Page Count: 448 Release Date: Aug. 1, 2023 Photo of author- credit - New York Times

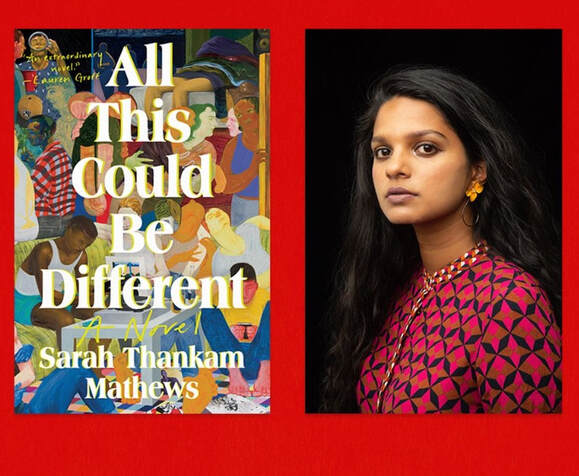

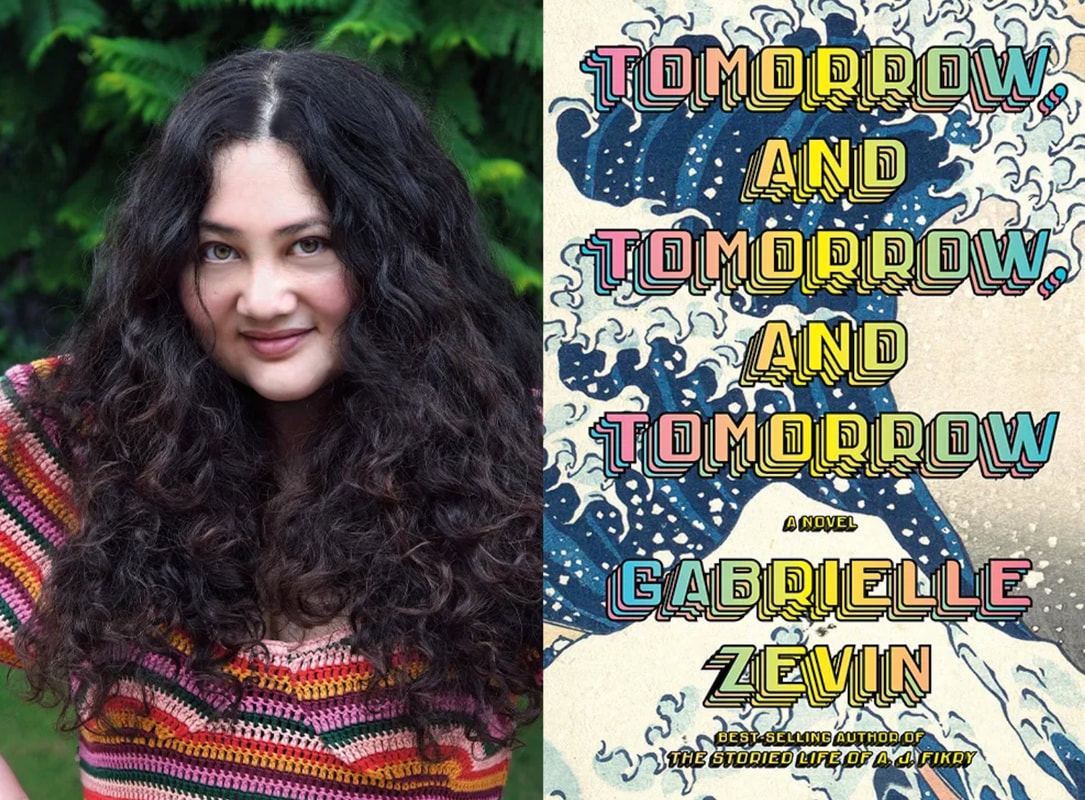

Strap in and get ready for this one, which definitely lives up to its early buzz in the book industry! Author Rebecca F. Kuang steps away from her established genre of fantasy to deliver a beguiling lit fic story of diversity, racism, cultural appropriation and plagiarism. The book focuses on a first-person account of June Hayward, a young white writer with aspirations to be majorly successful novelists. After one book that earned her no attention and dismal little sales, she becomes obsessively jealous of her former college classmate, Athena, a hugely successful, talented and popular Asian author. An unfortunate situation gives way to an opportunity for June to steal from Athena's not-yet-submitted manuscript and pawn off as her own. Even to her own surprise, she quickly lands a better agent and bidding war ensues for “her masterpiece,” The Last Front, a fictionalization about a little-known period in Chinese history. June and her agent decide to go with a hot-shot independent (white) publisher that will give her the attention she and her book deserve. Throughout the publishing process, staffers raise concerns of public perception to a non-Asian author tackling her topic and characters and request authentication, which June refuses to comply with. Since she is a young writer with the most sought-after manuscript, the issue is not pressed. Instead they compromise by deciding to tweak her name, giving it an Asian flare, Juniper Song. From that point on, she and her editor, Daniella widdle down at the story’s original strength and truth. Let the whitewashing begin as the below excerpt displays. Reading should be an enjoyable experience, not a chore. We soften the language. We take out all to “Chinks” and “Coolies.” “Perhaps you mean this as subversive, writes Daniella in the comments, but in this day and age, there’s no need for such discriminatory language. We don’t want to trigger readers.” We also soften some of the white characters. No, it’s no as bad as you think. Athena’s original text is almost embarrassingly biased; the French and British soldiers are cartoonishly racist… instead we switch one of the white bullies to a Chinese character, and one of the more vocal Chinese laborers to a sympathetic white farmer. This adds the complexity, the humanistic nuance that perhaps Athena was too close to the project to see. Juniper’s book strikes publishing gold and changes the trajectory of her career and life, at first for the better, then not so much. She will not only deal with the realities of online scrutiny and cancel culture, but eventually will have to grapple with her own deciept and inner demons. Will this bring her the fame and fortune that has "unfairly" eluded her? Since she researched some of the story and added to the manuscript, isn't it hers? Can only BIPOC writers tell BIPOC stories? Hasn't she been the victim of reverse discrimination? Readers will see how the answers to all of these questions/issues and more get explored in this page-turning thriller. Readers of all races and ages will be just as surprised and enthralled as they are entertained. Yellowface successfully joins ranks with clever dark comedy novels, like Interior Chinatown and Hell of a Book, that brilliantly have their stories deliver poignant messages of racism while allowing the readers laugh-out-loud moments throughout. The only thing that could have made this book even better, allowing for a full circle publishing situation, is if it had been published by Macmillan. Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang will be released on May 23, 2023 by Harpercollins Books All This Could Be Different debut novel by Sarah Thankam Mathews. This National Book Award nominee is a unique slice of life chronicling a young immigrant building a career and social life for herself in Wisconsin. Sneha is introspective, often quiet and torn between pursuing a career that would interest her versus what is just handed to her. As the first in her family to go to college and a first generation immigrant, she experiences a lot of self-imposed pressure for her job, money and lifestyle. She wants the respect of her boss and her parents' approval while securing enough funds to support her Midwest lifestyle and to contribute to their life back in India. Her thankless, low paying office job and her growing acceptance of preferring women over men, make it hard to keep up with appearances and enjoy the life she has fallen into. Sneha grows to appreciate her select few friends, a group of fun and fascinating millennials she attracts along the way between college and work. They help her be honest with what she truly wants, find her footing, and teach her how to stick up for herself in challenging situations. While seemingly nothing not much happens in this subtle All This Could Be Different, so much is going on with the protagonist and the story. It ultimately is a subtle, warm and dazzling saga of queer love, friendship, work, and precarity in twenty-first century America. It is both witty and wildly moving, leaving an indelible mark on every readers heart while showcasing Thankam Mathews as a refreshing new talent and a necessary literary voice. It's been a long time since a book has moved me to actual tears, but Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin has done just that. It did so not because it is overly romantic or remotely sappy, but rather because it is wonderfully written, with two main characters that are fully drawn and utterly engaging. Sam and Sadie meet as pre-teens while he is in the hospital and she, unbeknownst to him, is accumulating volunteer hours for a program through her synagogue. Although coming from very different worlds, a friendship is born, lost and re-born, spanning several decades, including when the two reunite in Cambridge, MA while in college.

It is there that they discover their shared passion for gaming, playing and designing them, and as such, they decide to collaborate on the creation of one. Ichigo was truly a labor of love that took most of their Junior year. Throughout the year, their friendship deepened although initially they did not divulge the deep emotions making up their lives. For Sam, in addition to being partially disabled, that meant withholding exactly when and how he loss his mother and why he had spent much of his youth being raised by his grandparents in LA. For Sadie, it was the current situation of being in an ill-advised and unhealthy relationship with her married professor. Helping to navigate their friendship while keeping up with classes and building a great game, was Sam’s affluent, but always affable and positive roommate, Marks. Although he knows nothing about gaming except playing them, Marks is Sam and Sadie's biggest fan. He was there for them both- buying meals, diffusing arguments, encouraging creativity, and underwriting the project. He was their rock and the glue that made them stick throughout that challenging year and then some. The three would garner so much success with that first game, they would go on to develop other games, enlisting the help of an entire staff, first in Cambridge, then back to LA. Author Gabrielle Zevin brilliantly explores the fragility of love and friendship, identity and disability. She does so through the vivid prose, stinging dialogue, and with the backdrop of the imaginative world of gaming. It's important to note, that you do not have to be into gaming at all in order to appreciate this story. As much as I was fully drawn into the characters and their individual and collective journeys, I even more so appreciated Zevin’s writing, plot development and witnessing her obvious personal growth as a writer. She quietly and solidly enter the indie bookstore scene in 2014 with the sweet and effective novel, The Storied Life ofA.J. Fikry, then in 2017 she showed her range with the socially relevant, yet often hilarious book, Young Jane Young. But Tomorrow takes her to a whole other level, or as Publisher’s Weekly puts it, “A-one-of-a-kind achievement.” photo by Magdalena Frigo

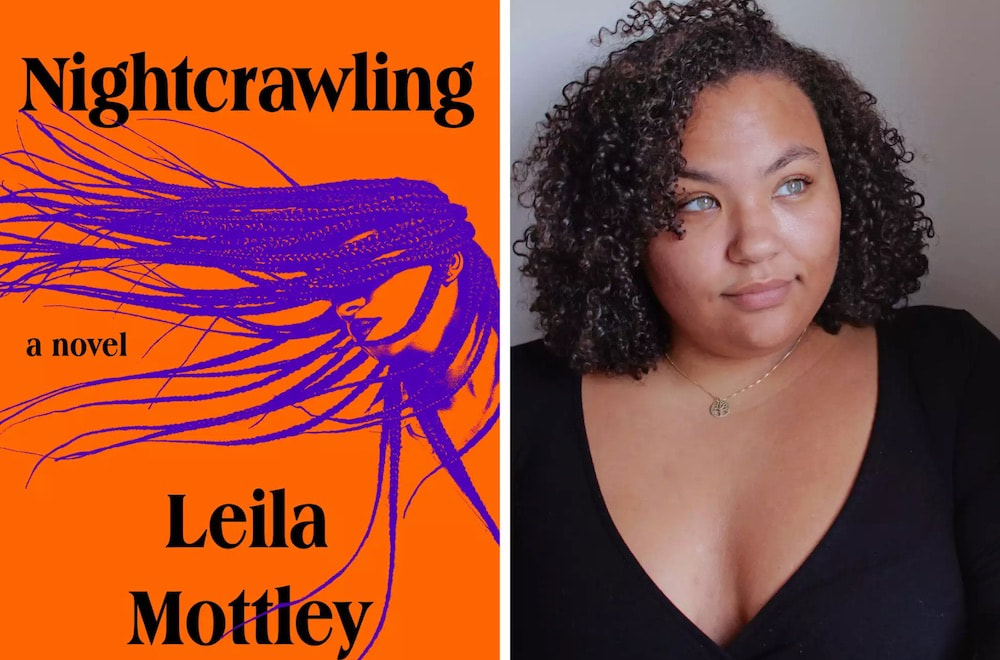

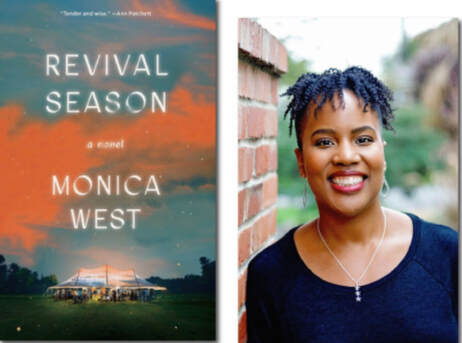

Nightgcrawling by Leila Mottley is not only a truly stunning debut novel from a very young author, accomplished beyond her years, but it is an vital story giving voice to the voiceless. The book’s protagonist, seventeen-year-old Kiara, who like her slightly older brother, Marcus, has dropped out of school and is barely scraping by to keep a roof over their heads in the absense of both their parents. Adversely impacted by death and prison, Marcus can’t seem to do anything but futily pursue a dream of a career in music. While this may spark joy and hope for Marcus, it does not help pay the rent or put food on the table. As such and while also trying to take care of a neighbor’s little boy who is neglected by his mother, Kiara bumps into perpetual unemployment which leads her to become a streetwalker to make ends meet. She’s ashamed by the path she has gone down. And knows she has to let her brother know. I think maybe today is the day I’ve been waiting for. The Day when Marcus decides he will straighten his. Spine and learn how to hold up a little of this life again. The day he’ll put his head in my lap and. Let me cradle him. Or he might even hold my hand, ask me why there are bruises tracing my chest. Some days it feels like I’m stuck between mother and chld. Some days it feels like I’m nowhere. I’ve got something tosay to him. I promised myself I would and I don’t remember most things mama taught us, but she always said we stick to our word. Not just mama. This whole city knows the one thing. You don’t do is break a promise. Just like you don’t take the last piece of chicken without asking every person old enough to your mamma if they it first. Unfortunately, Marcus doesn’t come through and Kiara’s streetwalking lands her in turning tricks among a corrupt group within the Oakland Police Dept. While Nightcrawling at times is an emotionally tough literary journey given its premise, it is also a novel I found myself fully engrossed with and finishing it relatively quickly. The fact that it can be emotionally challenging is large part credited to Mottley’s writing prowess. The first-person narrative effectively has you immersed in Kiara’s sad, destitue world, but also her strength and protective, mother-like quality that leads her to do anything to maintain the semblance of family with Marcus and Trevor. Although Kiara is the same age as the novel’s author at the time it was written (yep, Mottley is was only seventeen!), this is not based on her life. In fact, Kiara is a fictionalized character, but her story represents real events that were in the news in 2015. These events involving young Black women and the Oakland police served as inspiration, as mentioned in the Author’s Notes at the end of the book. Here is a sample: In 2015, when I was a young teenager in Oakland, a story broke describing how members of the Oakland Police Department, and several. Other police departments in the Bay Area, had participated in the sexual exploitation of ayoung woman and attempted to cover it up. This case developed over months and years and, even as the news cycle moved. on, I continued to wonder about this event, about this girl, and about the other girls who did not receive headlines, but nonetheless experienced the cruelty of what. Policing can do to a person’s body, mind and spirit … The stories of black women, and queer and trans folks, are not often represented in the narratives of violence we see protested, writtenabout, and amplified in most movements, but that does not erase their existence. Nightcrawling will prove to be one of the best books of 2022 for it’s rawness and intensity, yet undeniable poignancy, as well as marking the unearthing of a dazzling new and necessary voice in the world of fiction from Oakland Youth Poet Laureate (2018), Leila Mottley. Revival Season - While Revival Season by Monica West is a quick read, it is not necessarily an easy read. That is not to say it isn’t a well-executed, contemporary debut novel, because it is, but the subject matter about an abusive Southern Baptist preacher, is intense and heart-wrenching at times. The story’s main character, 15-year-old Miriam is the daughter of one of the South’s most prominent Black evangelists. As such, at the start of every summer, she and her family load up the family car and spend several weeks on the road, going from church to church for her father’s healing services. During this one fateful summer, Miriam sees her passionate preacher father in a different light as she observes his temper targeted towards not only herself and her mother, but congregants. Maybe even doubling vexing is hearing her father accused of abusing a young girl.

During that same revival season, Miriam learns that she may actually have the gift of healing her father may only be faking. Out of fear of her father’s jealousy, as well as his staunch belief that women cannot heal or have leadership positions in the church, she uses her “gift” sparingly and on the down low. With all the tumult of this particular season, Miriam’s belief in her father and religion is shaken to its core. Every few minutes, I caught Ma shooting glances at Papa. De he at all resemble the man she had married sixteen years ago? The way the story went, she was seventeen. When a. cocky, twenty-year-old boxer turned preacher came to her town as the Faith Healer of Midland. She gave her life to Jesus on the spot and married Papa six weeks later. We had lived under the canopy of that belief my whole life, eating and drinking faith in God first and Papa second, never questioning Papa’s healing abilities, the same way we never questioned the existence of the sun, even when it was hidden behind clouds. Our belief left no directives about what to do if our faith in Papa faltered. The story of Revival Season is simple, yet somewhat unique in its exploration of a young girl’s faith in the face of an abusive father and a life-altering decision. It is both interesting and laudable that although a Black family is at the center of this story, race and racism are not. It is themes of man versus religion, and women versus a dominant man that is universal that West chooses to navigate. As a writer, her style is pared down and straight forward, maybe at first glance, even a bit underwhelming, with little to no lush, lyrical or memorable lines, per se. There is no especially strong sense of place although the spaces the family inhabits are screaming for atmospheric descriptions. That said, with a debut such as this, West undeniably shows signs of an emerging talent to keep an eye on. Publisher: Simon & Schuster |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed